On October 10, 1939, five weeks after Great Britain declared war against Germany, an announcement was made in Canada that an agreement had been reached among representatives from Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom that a joint air training plan would be put into effect in order to provide the urgently needed Commonwealth aircrew. The agreement was signed on December 17, 1939, after tough negotiations between Prime Minister Mackenzie King and the British representatives. The British had expressed considerable doubt as to the ability of Canada to carry the scheme through but finally, after a period of difficult manoeuvering, they agreed that it would be administered by the staff of the Royal Canadian Air Force.

To meet its heavy training commitment, the R.C.A.F. was expanded and Air Commodore R. Leckie, who was serving with the Royal Air Force, was brought back to Canada to direct the plan. All four partners were represented on an advisory board chaired by C. G. Power, Canada’s Minister of Air, and each had a voice in its direction. The program of what was now officially called The British Commonwealth Air Training Plan and production was scheduled to be completed in two years. Airdromes would be opened all across Canada, training pilots, navigators, flight engineers, air gunners and bombers.

The history of #31 Service Flying Training School is not one of a typical B.C.A.T.P. school as it was destined to become the home of the first R.A.F. pilot training school moved to Canada from England.

The story begins in the small town of Gananoque, 18 miles east of the city of Kingston. An Army camp had been established in town during the Great War and its peacetime artillery militia battery had served with distinction during the war, so it was that within a few weeks of the initial announcement of war, that the mayor, W. J. “Billy” Wilson, wrote to the Honourable Norman Rogers, Minister of National Defense, and asked that he have Gananoque in mind with respect to contributing in some way to the war effort. The mayor also began negotiating with the Leeds Member of Parliament, the Honorable H. A. Stewart, offering the suggestion that an air training centre be established in the immediate district.

A committee of local businessmen was formed and the reply from Ottawa that the matter would receive investigation encouraged them to pursue it further. The Department of Transport requested that a survey of the surrounding area be done with the view to find ground which would be suitable for the training of pilots. Mr. Jim Delaney did an aerial survey and submitted photographs of the parcel of land he considered to be the most suitable. It was in the area known as South Lake near the boundary line of the townships of Pittsburgh and Front of Leeds and approximately six and one-half miles northwest of the town. Mr. Delaney described the farm fields as a ‘natural’ location for an air field.

The Transport Department made a preliminary survey of the land and the prospects looked very good. It even appeared possible that a central airdrome would be constructed at South Lake with auxiliary fields being established near Kingston and Brockville to the east. The size of the area under consideration was between 600 and 1000 acres, and there was no large field in operation between Montreal and Toronto except the Kingston Flying Club field. This property was ideal, as far as anyone could see, but after waiting for two months it was learned that the government had begun to take up options on land near Collins Bay, approximately five miles west of the city of Kingston.

On April 3, 1940 the Minister of Defense made the official announcement that a service flying training school would be established in the Kingston area by May of 1941, with nearly one thousand staff and pupils. This was the earliest date it was expected that the school could be ready for operation. The 745-acre tract of land chosen for the site was on the shore of Lake Ontario, just east of Lemoine’s Point. The owner, Mr. James Henderson, was advised by Ottawa to vacate his farm by June 1, 1940. The cost of the airdrome would be $1,186,700.00, and Canada said it would do it alone.

An experienced pilot, Mr. Delaney expressed the opinion that the site might be impracticable for pupils as the fog in that area was regular due to the proximity of the lake and nearby marshes. He stated it was his belief that “it would be a hazardous undertaking to train new members under such conditions.” He also suggested that the South Lake site might be used as a training field rather than an emergency field as was now proposed. This did come to pass although it retained the designation of No. 1 Relief Landing Ground. The construction of two runways at the South Lake site began on June 4, 1940.

The initial R.C.A.F. designation for the airdrome was #10 S.F.T.S., but the deteriorating situation in Europe changed the original plan. France had fallen and now the British government sought permission to transfer to Canada en bloc a number of existing schools in order to remove them from what had become an active war front. Due to the increasing urgency for aircrew, the construction plan was now compressed into a one-year programme.

Construction of the Kingston airdrome was one of the most gigantic construction works that had ever been undertaken in Eastern Ontario, with more than 700 mechanics and labourers employed around the clock. Trees and brush on the 745 acres had to be cut and all and brush on the 745 acres had to be cut and all the stumps cleared before the area could be graded, drained, smoothed and then seeded in order to build the runways and taxi strips. In spite of wet weather, the work advanced so rapidly that it was thought possible that the airdrome could be ready for training as early as October 1940, six months ahead of schedule.

The firm of McGinnis & O’Connor were contracted to level the ground and fence the entire area. They would also build the runways, which were to be 2500 feet long and 150 feet wide. Mr. T. A. McGinnis expected the firm would be able to complete their work in 90 working days, and commented: “The men have put their backs to the wheel and I never was so proud of a gang in my life as I am of these men. They realize the urgent need for trained airmen and I have not heard one complaint about working conditions or long hours.”

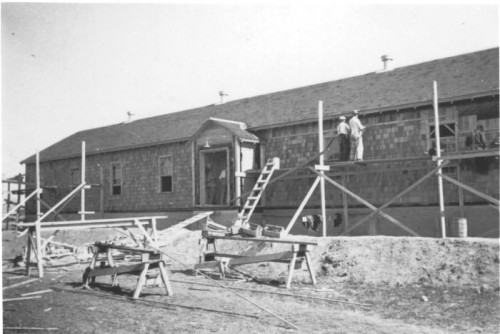

The contract for buildings was awarded to A. W. Robertson Ltd. of Toronto and it was expected that they would be able to complete construction not later than the first of October. They were to be temporary buildings of frame construction, with asphalt brick sidings and cedar shingles. The station would have five hangars measuring 112 x 160 feet with two lean-tos 20 feet wide. The other buildings, which were to be constructed south of the hangars, included: one officers quarters and one officers mess; two quarters for non-commissioned officers, along with one mess; six quarters for the airmen, two messes and a canteen. Similar accommodation was built for the civilian workers on the base.

The station required a recreation building, a sports field and pavilion, a ground instruction school, a drill hall and a supply depot, each measuring 112 x 160 feet, a guard house, a watch house, and a 34-bed hospital. In addition, the training school would require storage tanks for about 20,000 gallons of gasoline and storage space for explosives. Permanent roads connecting the various buildings were built. A rock quarry in the area was floodlighted to enable a night shift to continue work removing the stone that formed the runways.

The announcement was made in August 1940 that the site west of Kingston had been chosen as the home of 7 S.F.T.S in Peterborough, England. It had the distinction of being the first R.A.F. school transferred to Canada. As well, it had the added distinction of being one of the few stations engaged in training pilots of the Royal Navy Fleet Air Arm. These aerodromes would be governed by the Visiting Forces Act, and would keep their national identity and, to a limited degree, their autonomy. The schools were to act in combination with the Royal Canadian Air Force, which would have extensive powers over them. On September 15, to avoid confusion with the B.C.A.T.P. schools, the airdrome was renumbered 31, thus establishing a sequence of numbering for the R.A.F. schools in Canada.

The First Echelon was formed under the command of Squadron Leader D. McC. Gordon and, on August 28, 1940, the unit left Peterborough by rail for Liverpool where they embarked H.M.S. “DUTCHESS OF RICHMOND.” During the night, the port of Liverpool was attacked by enemy aircraft and one stick of bombs fell close to the ship, startling the men who were battened down in tightly-packed quarters. No casualties or damage occurred. In accordance with security practices, the ship’s destination was not made known to the men but, as they had been issued tropical kit, they believed they were being posted to a base in North Africa. A new front had opened in June 1940 when Italy declared war on Britain and France, which made it likely that they were being posted to the Middle East Command.

Without escort, the ship spent 10 days zigzagging about the Atlantic Ocean. After a few days at sea, the airmen were informed that they were being transferred to Canada and that their destination was Kingston, Ontario. This announcement was a complete surprise and an ex-R.A.F., who returned to live in Kingston, said their initial reaction was one of stunned silence. Then the first puzzling question was heard: “Where is Kingston?”

He recalled what it had been like to leave loved ones in danger due to air raids and the still very real possibility of an invasion by the Germans: “Most of the airmen were disappointed, and even ashamed, to have been temporarily removed from the war.” The airmen had already experienced the fear of being attacked when the Peterborough station was bombed and strafed by German aircraft and this was the description of his reaction to such an attack: “I ran up to the roof taking a rifle, the only weapon there was. I flung myself down, propping the rifle on the parapet and began shooting at the planes as they came over. In all the excitement, I was too busy to be frightened but after it was over and I stood up, I could see all around me the jagged tears in the asphalt where it had been peppered with machine gun fire. Then the fear hit me.

Canada and dry land were now in view but after first docking at Halifax, the DUTCHESS OF RICHMOND continued to Montreal where the seasick, water-weary men finally disembarked and boarded a train for Kingston. Unfortunately for the tired men, the coaches were old and added nothing to their comfort. This trip was described in a story printed in ‘The Pioneer’, excerpts below.

“THE ENTRY OF THE GLADIATORS” (1940 version)

“The train journey from Montreal was uneventful except for the unceasing howls of the engine and the cacophonous din resulting from the failure of Canadian railways to fit their carriages with buffers. It was suggested by a brainy ‘erk’ that the engine was fitted with a double-barrelled boiler, one for power and one for noise.”

This was not the Canada they had expected to see, he said: “We were very disappointed by the complete absence of Redskins, cowboys and broncos along the route.”

On September 10, upon their arrival at the Cataraqui Crossing (now on Gardiner’s Road), the R.A.F. unit was greeted by officers of the R.C.A.F., among them were Group Captains Sully and Mackworth. Adding to their disenchantment, all the airmen could see as they lined up were acres and acres of farm land and cows grazing in the fields. In the distance, they saw a red-roofed stone building which resembled a castle. Recalling that day, an ex-airman said he had no way of knowing that after the war he would return to Canada and work for nearly thirty years in that ‘castle’, which was, as they soon learned, the Collins Bay Penitentiary.

As usual, transport had been provided for officers only, so the hot and weary airmen trudged along the dusty road carrying full kit and heavy greatcoats. In the same author’s words:

“The arrival at Cataraqui siding was marked by further obligatos in the aforementioned dulcet tones. These were obeyed with alacrity and there followed yet another roll-call. Bringing nostalgic memories of Uxbridge, there came the order to move off: ‘Slope kitbags! Quick march!!’ The day was warm, the roads were hot and dusty to boot and to throat. Attempts to sing were ineffectual when thick dust lined the larynx.”

Finally, to their relief, they saw a large sign. “Further investigation revealed a gate, but still in vain did we search for a sign of a camp. All that met our gaze was dust, confusion, mechanical navvies, holes in the ground, and more dust. Eventually our billets (sic) were located and, after removing carpenters and painters, we entered into occupation. Plumbers were conspicuous by their absence.”

The description of the conditions the men encountered was not exaggerated as is shown in the photographs below and on the next page. What a discouraging sight for the men after a long sea journey, a tiring train ride, and a long, hot walk.

One of the airmen recalled the period before the station was up and running:

“The camp did not have sewers and the change of diet and water had the usual effect on the men, and the unfortunate ones were assigned to gather the effluent in barrels on the back of a wagon drawn by a mule. This was promptly named, ‘The Bombay Mail.’ One day, one of the huge barrels fell off the wagon with a great crash just outside the Commanding Officer’s office. Everyone thought it was hilarious, and appropriate – except the C/O, of course.”

Once all the facilities were operating, there was yet another complaint. The washrooms in the permanent barracks they had so recently left had been equipped with bathtubs, but now they found they had showers only. In the beginning some made-do with a sponge bath rather than adapt; they covered the drain and splashed themselves with the small amount of water in the bottom of the stall.

The officers’ mess was in a stone farmhouse on the lake side of the Front Road: no plumbing, but great parties, one of the ladies said. They had an incredible chef and so had the advantage of having the most and best parties, which only caused more dissension between the ranks. This was aggravated by the very real British class system which followed them to a democratic Canada.

The bright young ladies of Kingston began to find opportunities to meet the instructors and one reminisced about the great fun they had and described these veterans as experienced young men who lived life to the fullest, with a few bordering on the flamboyant. Having survived the Battle of Britain, they were here for a ‘rest cure’, although training inexperienced pilots who had just graduated from initial training hardly seemed compatible with relaxation but as ex-instructor Trevor Dossett said: “At least, I didn’t have to be watching my tail all the time.

The strength of the unit was 18 officers, 3 Warrant Officers, 3 Flight Sergeants, 12 Sergeants, and 280 Corporals and Other Ranks. Flying Officer G. G. Morrow of the R.C.A.F. was assigned to the station on September 12 as liaison officer.

Training would have to be done in the only aircraft available, which was the obsolete Fairey Battle Bomber. It was not suitable for training but would have to suffice until the new aircraft, the North American Harvard, was manufactured in sufficient numbers to be delivered to the sixteen service flying training schools across the country. In order to test the aircraft prior to delivery, Flying Officer D. C. Skene was attached to the Fleet Aircraft Corporation and on October 2 he returned with the first aircraft from Fort Erie.

An ex-R.A.F. sergeant recalled that the first Fairey Battle Bombers delivered to the station had been in service with the British Expeditionary Forces in France and still bore the evidence of machine gun fire. Describing the arrival of these aircraft, he said: “It took us a little while before we got aircraft in. It was a case of the aircraft being dismantled in England and being sent over. Sometimes the fuselages were separate from the engines and we would get a bunch of fuselages and no engines and vice versa. It took us quite awhile to get organized.”

Reconstruction at Sandhurst Relief Landing Field in November 1940

In September 1939, the R.A.F. possessed approximately fifteen hundred Fairey Battles, which were described in one book as a “coffin for its gallant crews in the clashes with the Luftwaffe in May 1940.” The wonder is that more crashes and fatalities didn’t occur here before they could be dismantled once again.

Fourteen pupils arrived from #4 Elementary Flying Training School, Windsor Mills, Quebec on October 6 and on the following day, twenty-one arrived from No. 3 E.F.T.S. London. On November 1, 1940, the strength of the unit was: 23 officers, 2 Warrant Officers, 3 Flight Sergeants, 12 Sergeants, and 309 Corporals and Other Ranks. During a bad snowstorm on 10 November 1940, a group of 170 Other Ranks arrived from 7 S.F.T.S., with the following instructors: Flight Lieutenants J. H. White and J. Hewson; Flying Officers R. D. H. Ellis, S. C. Weir-Rhodes, J. R. Wood; Pilot Officers E. H. Jones, E. Ciemow, G. Holloway, L.I. Cockerham, R. A. Jackson, H. R. Pooley and R. Garnie.

On the 12th, the following officers arrived: Squadron Leader E. H. E. Cross, Pilot Officer J. W. Bradley, Warrant Officer H. Curtis.

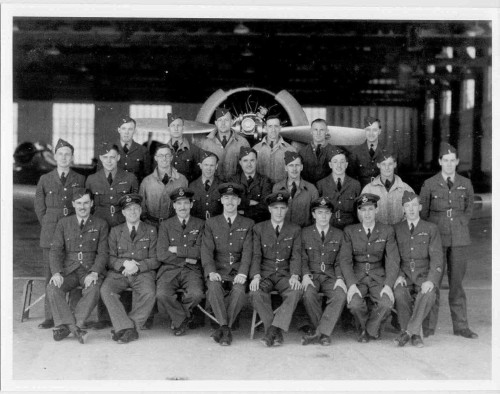

This is a photo from the first groups to arrive at #31.

Only two of the officers were identified: front row left, John Leishman and to his

right, Frank Holland, who arrived at the camp on 25 January 1941. He married while at Kingston and returned to operations in England and France.