From the Admiralty Official F.A.A. book 1943: These young men had “fought the enemy flying from frozen airfields, rolling carrier decks and blistering desert sands. The crippling attack on Italian warships at Taranto, perhaps, has been the greatest achievement to date in this war for the tough young men Britons who fly the Fleet Air Arm’s planes. They were at Narvik and helped to sink the Bismarck; they provided air cover for convoys to Malta and Murmansk; they guarded the lifeline across the Atlantic and helped pave the way for the landings in North Africa, Sicily and Italy. They bombed enemy ports, airfields, factories and fortifications, trailed enemy fleets and protected our own, sowed mines in estuaries and harbours and engaged on fighting operations from Petsamo down to the Falkland Islands.

They had accomplished all this with small numbers so were flying constantly. Often they existed with very little sleep as they had to stand duty as well as fly. It is possible their skill deteriorated as they became exhausted. With larger numbers, the U.S. were able to replace entire groups after several months of combat flying but the British did not have the resources for replacements on that scale. John Winton in the Forgotten Fleet wrote that by August, “Squadrons included many very young men on their first operational tour, some had completed only a dozen previous deck landings and a number had less than 150 hours solo flying on type.” (The British Pacific Fleet carrier operating statistics in July and August shows that the combat losses as percentage of offensive sorties was 2.38, 48% higher than the U.S.)

In his book, “Wings of the Morning,” Ian Cameron noted that the strain of flying from a carrier by night had been assessed by medical experts as four times as great as by day because take-off and landing was more difficult in the dark and there was more risk of failing to locate a carrier at the end of one’s patrol. The chances of survival in the event of a crash over the side or a ditching became virtually non-existent. He wrote: “The wonder is not that the occasional crew cracked up, but that any of them survived at all. The flight deck was turned into a battleground: a battleground awash with mountainous seas and continually lashed by sixty-knot squalls of wind and rain; a battleground on which on every take-off and landing the lives of the aircrew hung trembling in the balance.”

He described how, in a two-week period of U-boat hunting, 825 Squadron flew close to 300 hours, made 122 deck landings and investigated getting on for fifty contacts. He estimated that 85% of the flying was done by night and 90% of it done in appalling weather. In terms of aircrew fatigue, every hour was equal to about seven hours of normal fair-weather flying.

The end of the war in Europe was in sight. The news on 30 April 1945 was that Adolph Hitler had shot himself as Russian troops fought to within yards of his bunker. A week later, May 7, a surrender document was signed and the next day, May 8, a cessation of fighting took effect at 11.01.

On July 1941, Winston Churchill declared, using his famous V for Victory sign: “The V sign is the symbol of the unconquerable will of the occupied territories and a portent of the fate awaiting Nazi tyranny. So long as the peoples continue to refuse all collaboration with the invader it is sure that his cause will perish and that Europe will be liberated.”

EUROPE FREE

Kingston Greets Victory News with

Tremendous Enthusiasm.

The loud clanging of the bell at the city hall broke the silence of the Monday morning with its glad tidings. Others quickly followed suit and the bells on St. James Church, Sydenham Street United Church, and St. Andrews rang forth in triumphant jubilation. The air-splitting whistles of the Canadian Locomotive Company plant and the shipyard burst forth in gusty shrieking echoed by the blatant whistles of the boats at the Kingston docks. On Princess Street, hastily decorated trucks rolled along over-burdened with cheering hitch-hikers and children who were released from school.

Confetti showered down from office buildings consisting largely of torn paper and improvised streamers. Office and plant workers streamed out of their places of business within moments of the great announcement. Flags were unfurled. A service of thanksgiving will be given in each church this evening.

A mammoth V-E parade on May 8 was one of the best ever staged in Kingston. Thousands of spectators lined the route from the Fair Ground to the Cricket Field. Floats of all sizes and description, private cars and bicycles, horsemen, pony carts, and pedestrians participated. The several block-long parade ended with a fireworks display.

Three of the instructors congratulating each other at the Gan Airport. One of the instructors was A. E. Wigley, R.A.F.; another was F/O Murray Linkert who arrived at No. 31 on June 30, 1944. He was recommended for the Air Force Cross by the C/O, S/L Ross Truemner (May-Aug. 1945):

“As a Flight Commander this officer has shown immeasurable ability in organizing and is outstanding among his fellows as a pilot and flying instructor. His skill and devotion to duty have been exceptional in all respects. His excellent contribution to specialist training is an inspiration to all.”

The war in Japan surely wouldn’t last much longer, regardless that the Emperor said there would be no surrender and they would fight to the end of every man, woman and child. The word “surrender” wasn’t in their vocabulary but everyone knew they would eventually be beaten by the Americans. The U.S.A. had the resources and the factories that could keep up an unending supply of ships, airplane and ammunition, and Japan didn’t.

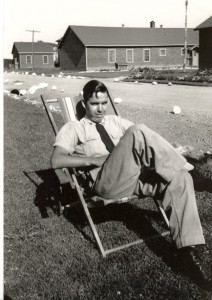

Training was winding down at all stations across Canada. After V. E. Day, Squadron Leader G. Ross Truemner, A.F.C., arrived at Gananoque Airport to take over command. He had been a multi-engine instructor at 16 S.F.T.S. near Hagersville and most of his flying hours were on Ansons. The C/O at Kingston got word that things had become too relaxed at “The Farm” and spent a half-day making everything miserable for everybody. The chief instructor was sent to check them out and after a week observing the training schedule they had adopted, he was impressed and assured them that the C/O wouldn’t be bothering them again. He wasn’t impressed with the lawn chairs though. (Dick Caughey of Pittsburgh Township shared this photo of himself.)

Life had wound down but had not stalled: there were still seventy Fleet Air Arm pupils in training.

Three officers serving at No. 14 were awarded the Air Force Cross in June: F/O Clayton Arthur Haskett and S/L Robert Hewitt, R.A.F., and F/L A. W. Barton, R.C.A.F. of Cobourg. F/L D. A. Henderson, R.C.A.F., was awarded the King’s Commission for Valiant Service in the Air. He had graduated as Sergeant Pilot at No. 31 and had been an instructor at Aylmer, Ontario.

Capt. R. W. Hardy, Canadian Army

F/Lieut. J. W. Frizelle, R.C.A.F.

20 June 1945

The Last Fatal Accident in the C/O’s Diary

This tragic accident was avoidable and it is extremely sad that it took the life of the Canadian Army officer so close to the end of the war. It occurred during joint air force and army manoeuvres on the Scenic highway, two miles east of Mallorytown Landing on June 20. Capt. R. W. Hardy, who was stationed at Barriefield and F/L J. W. Frizelle from No. 14 S.F.T.S. were instantly killed, and a passenger in the plane, LAC Saul Katzman of Toronto, was injured.

The Whig-Standard reported:

“When the accident occurred, the soldiers under training lay in the ditch to the north of the north lane of the highway and fired blanks at the planes as they flew over ‘bombing and strafing’. That part of the manoeuvre was nearly over when Capt. Hardy decided explosions being set off in the water to the south (simulating bomb bursts) were sending columns of water too near some of the low- flying planes (five Ansons and five Harvards). In an effort to warn the planes away, he climbed on top of the cab of the recovery truck and, crouching there,

attempted to wave them away. The plane piloted by F/L Frizelle, of Toronto, was apparently flying in at the same height as the others, an estimated fifty feet above the ground, but just before passing over Capt. Hardy, the right wing dipped sharply striking him and the top of the cab.”

Captain Hardy’s assistant, Lieut. J. M. Davies, said, as he looked up from his position on the ground, he saw a figure he presumed to be the pilot crouching over in the cockpit and moving his hands as if pulling on the controls. The right wing of the plane, which had dropped to a seventy-degree angle, struck the boulevard, digging up the turf, then the nose dug in and the plane bounced to the north ditch where it came to rest.

Captain Hardy and his wife, Joyce Gwendolyn, had come to Kingston from Vancouver two years ago. Captain Robert Walton Hardy, R.C.E.M.E., was 32 years of age. His parents were Sidney W. and Louise Hardy of Vancouver. He was buried with full military honours at the Cataraqui Cemetery.

F/L John Wilson Frizelle, R.C.A.F., age 27, was survived by his wife Audrey Donna Frizelle of Toronto. He was the son of John Wilson and Florence Frizelle, Toronto and is buried at St. John’s Norway Cemetery, Toronto. He was widely known as a former Toronto Balmy Beach football and paddling star.

The accidents continued at No. 14 S.F.T.S., but no fatalities. In July, a Harvard piloted by A/LA J. F. Sargent caught fire in the air and crashed between Collins Bay and Westbrook. Fortunately the pupil parachuted safely from the plane. An instructor and pupil received slight injuries on July 18 when their aircraft burned after making a forced landing near the west end of Wolfe Island. Again later, P/O H. V. McLean, Ottawa, and A/LA H. S. Honsberger, Toronto, were dazed when their aircraft crashed Wolfe Island. Mrs. Alec Sexsmith and another woman dragged them from the plane, which was completely destroyed by an explosion immediately afterwards.

14 August 1945

WORLD PEACE NOW REALITY

The world rejoiced as huge headlines announced the end of the war in the Pacific. It took the dreadful bombings at Hiroshima and Nagasaki to finally bring an end to the war. After nearly six years of separation and loneliness for servicemen and families, telegrams bearing news of the tragic loss of loved ones, and news stories of death and destruction, peace was now a reality.

At No. 14, on V-J Day August 15, celebrations combined with the C/O’s Sports Day made the day an enjoyable one for the personnel and their guests. The day’s programme consisted of track and field events, along with sailing races at the waterfront, topped off with an exhibition softball game. The day’s programme was climaxed by a station dance in the Recreation Hall with the station orchestra providing the music.

7 September 1945

Today No. 14 S.F.T.S. officially closes

and the airport

reverts to its original name

“Norman Rogers Airdrome”

During the nearly five years of training, the R.A.F. and R.C.A.F. graduated 1,846 Fleet Air Arm pilots from the United Kingdom and the Commonwealth countries at the Collins Bay station. From the time the R.C.A.F. took over in August 1944 until January 1945, when the station was transferred from No. 3 Air Command, Montreal, to No. 1 Air Command, Trenton, a total of 606 pilots graduated. After January, 282 more had come and gone. Approximately 200 were in training when the order to halt such training was received.

In September, a report said: “5,296 R.A.F. and F.A.A. received training in R.A.F. schools in Canada and were graduated before July 1942 when these schools became part of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan. Peak for the plan was reached in January 1944 when there were 73 B.C.A.T.P. flying training schools in operation and 24 R.A.F. transferred schools in operation.”

The financial experts calculated the cost of the B.C.A.T.P. to be $2,231,129,029. Canada’s contribution amounted to 72% of the air training cost. When hostilities ended, airfields built especially for the B.C.A.T.P. were either absorbed into the country’s air transport system, used as industrial airports and centres of local flying, or for purposes other than flying. Some fell completely into disuse.

At Gananoque, former R.A.F. instructor Doug Wagner made one end of the recreation hall into living quarters for himself and his wife and began a school for training pilots. The Kingston airdrome quickly became a centre for local flying and later Doug closed his school and began a commercial air service in Kingston. The Gananoque Airport Commission was formed and little use was found for the former training field until approximately thirty years later when a group of parachutists began using the field on a regular basis. It now is the home of the Gananoque Sport Parachuting Centre.

In 1981, two members of the R.C.A.F. Association 416 (Air Vice Marshal Godfrey) Wing at the Norman Rogers Airport, Doug Wagner and Phil Quattrocchi, had a dream to erect a memorial to the servicemen who trained there and, in many cases, paid the supreme sacrifice. At one time, after the war, it would have been possible to buy a surplus Harvard aircraft for about $100.00, but no one in Kingston or Gananoque had the vision to commemorate the important position they had held during the war with such a memorial. Smiths Falls, a town with no air training scheme, has a Harvard on display in the park as one enters the town on Highway 15.

It was now 36 years later and Harvards were scarce and it appeared that none which could be used for the memorial was to be found. Finally, the remains of the Harvard in which A/LA Geoffrey Fitton crashed was retrieved from the waters off Collins Bay. Unfortunately, as it was exposed to the air in the hangar where it had been placed, the aluminum disintegrated overnight. Finally they were able to piece together a Harvard which was dedicated at a reunion held in September 1985 with nearly 800 in attendance.

Former members of the Navy made plans to erect a memorial honouring the F.A.A. pupils who died while training at Kingston and Gananoque. It was dedicated on the Battle of the Atlantic day in May 1992. The number of F.A.A. dead on the plaque is 23, but this is short the four who weren’t buried in Kingston. They were: A/LA McCulloch who crashed at Seeley’s Bay in June 1941 and is buried in Vancouver, and three pupils whose bodies weren’t recovered from the Lake – A/LA J. C. Moore, June 15, 1942; Lieut. L. C. Edwards November 28, 1942; A/LA E. Skorrow July 5, 1944.

Approximately 150 former pilots who had trained here marched to the site and three Harvards flew over in salute. One of the visitors was ex-F.A.A. Gordon Prentice of Altrincham, Cheshire, wrote this rhyme in a letter to the editor of the Whig-Standard:

“Someday I’m going to journey back to Kingston,

Though it may be at the end of my day,

Just to see the moon rise up on Gananoque

And the sun go down on dear old Collins Bay.”

“On a December evening in 1944, among a gathering of young British Royal Navy pilots who had that day been presented with their wings at 14 S.F.T.S., Collins Bay, I sang lustily the above parody to the tune of Galway Bay. Now, forty years on, I am going to make that sentimental journey. Early in October, I shall drive into Kingston to renew once more my acquaintance with the city that was my home for a brief period of the Second World War.”

And so ends the story of Fleet Air Arm pilot training at Kingston and later at Gananoque. It is a unique story due to the fact that No. 31 was the first R.A.F. school transferred to Canada. Also, importantly, until 1944 it was the only school in Canada training Fleet Air Arm pilots, and later the first one graduating pilots for the Royal Canadian Navy Fleet Air Arm. The unit struggled from the beginning to get the station established and it wasn’t until the new Harvard aircraft replaced the Fairey Battle Bombers that training matched the arrival of courses at the station. As one of the R.A.F. men said: “If Hitler had known how ill-prepared and ill-equipped we were, he would have invaded.”